After a stint at the Obama Energy Department, Steven Koonin reclaims the science of a warming planet from the propaganda peddlers.

**

**

By Holman W. Jenkins, Jr., April 16, 2021 2:20 pm ET

Barack Obama is one of many who have declared an “epistemological crisis,” in which our society is losing its handle on something called truth.

Thus an interesting experiment will be his and other Democrats’ response to a book by Steven Koonin, who was chief scientist of the Obama Energy Department. Mr. Koonin argues not against current climate science but that what the media and politicians and activists say about climate science has drifted so far out of touch with the actual science as to be absurdly, demonstrably false.

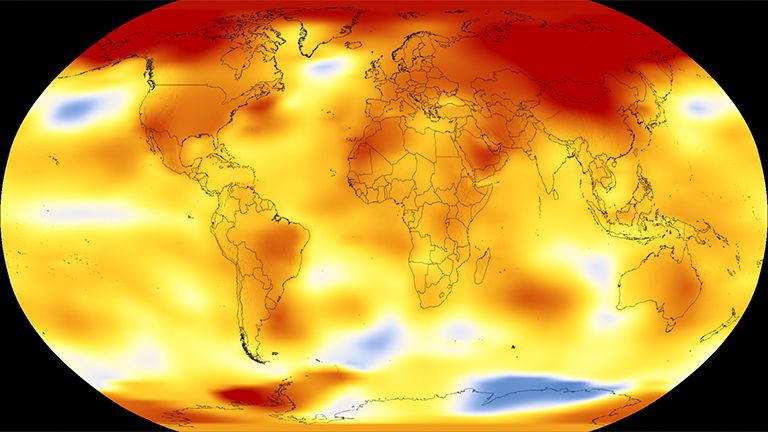

This is not an altogether innocent drifting, he points out in a videoconference interview from his home in Cold Spring, N.Y. In 2019 a report by the presidents of the National Academies of Sciences claimed the “magnitude and frequency of certain extreme events are increasing.” The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is deemed to compile the best science, says all such claims should be treated with “low confidence.”

In 2017 the U.S. government’s Climate Science Special Report claimed that, in the lower 48 states, the “number of high temperature records set in the past two decades far exceeds the number of low temperature records.” On closer inspection, that’s because there’s been no increase in the rate of new record highs since 1900, only a decline in the number of new lows.

Mr. Koonin, 69, and I are of one mind on 2018’s U.S. Fourth National Climate Assessment, issued in Donald Trump’s second year, which relied on such overegged worst-case emissions and temperature projections that even climate activists were abashed (a revolt continues to this day). “The report was written more to persuade than to inform,” he says. “It masquerades as objective science but was written as—all right, I’ll use the word—propaganda.”

Mr. Koonin is a Brooklyn-born math whiz and theoretical physicist, a product of New York’s selective Stuyvesant High School. His parents, with less than a year of college between them, nevertheless intuited in 1968 exactly how to handle an unusually talented and motivated youngster: You want to go cross the country to Caltech at age 16? “Whatever you think is right, go ahead,” they told him. “I wanted to know how the world works,” Mr. Koonin says now. “I wanted to do physics since I was 6 years old, when I didn’t know it was called physics.”

He would teach at Caltech for nearly three decades, serving as provost in charge of setting the scientific agenda for one of the country’s premier scientific institutions. Along the way he opened himself to the world beyond the lab. He was recruited at an early age by the Institute for Defense Analyses, a nonprofit group with Pentagon connections, for what he calls “national security summer camp: meeting generals and people in congress, touring installations, getting out on battleships.” The federal government sought “engagement” with the country’s rising scientist elite. It worked.

He joined and eventually chaired JASON, an elite private group that provides classified and unclassified advisory analysis to federal agencies. (The name isn’t an acronym and comes from a character in Greek mythology.) He got involved in the cold-fusion controversy. He arbitrated a debate between private and government teams competing to map the human genome on whether the target error rate should be 1 in 10,000 or whether 1 in 100 was good enough.

He began planting seeds as an institutionalist. He joined the oil giant BP as chief scientist, working for John Browne, now Baron Browne of Madingley, who had redubbed the company “Beyond Petroleum.” Using $500 million of BP’s money, Mr. Koonin created the Energy Biosciences Institute at Berkeley that’s still going strong. Mr. Koonin found his interest in climate science growing, “first of all because it’s wonderful science. It’s the most multidisciplinary thing I know. It goes from the isotopic composition of microfossils in the sea floor all the way through to the regulation of power plants.”

From deeply examining the world’s energy system, he also became convinced that the real climate crisis was a crisis of political and scientific candor. He went to his boss and said, “John, the world isn’t going to be able to reduce emissions enough to make much difference.”

Mr. Koonin still has a lot of Brooklyn in him: a robust laugh, a gift for expression and for cutting to the heart of any matter. His thoughts seem to be governed by an all-embracing realism. Hence the book coming out next month, “Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters.”

Any reader would benefit from its deft, lucid tour of climate science, the best I’ve seen. His rigorous parsing of the evidence will have you questioning the political class’s compulsion to manufacture certainty where certainty doesn’t exist. You will come to doubt the usefulness of centurylong forecasts claiming to know how 1% shifts in variables will affect a global climate that we don’t understand with anything resembling 1% precision.

His book lands at crucial moment. In its first new assessment of climate science in eight years, the U.N. climate panel—sharer of Al Gore’s Nobel Peace Prize in 2007—will rule anew next year on a conundrum that has not advanced in 40 years: How much warming should we expect from a slightly enhanced greenhouse effect?

The panel is expected to consult 40-plus climate computer simulations—testament to its inability to pick out a single trusted one. Worse, the models have been diverging, not coming together as you might hope. Without tweaking, they don’t even agree on current simulated global average surface temperature—varying by 3 degrees Celsius, three times the observed change over the past century. (If you wonder why the IPCC expresses itself in terms of a temperature “anomaly” above a baseline, it’s because the models produce different baselines.)

Mr. Koonin is a practitioner and fan of computer modeling. “There are situations where models do a wonderful job. Nuclear weapons, when we model them because we don’t test them anymore. And when Boeing builds an airplane, they will model the heck out of it before they bend any metal.”

“But these are much more controlled, engineered situations,” he adds, “whereas the climate is a natural phenomenon. It’s going to do whatever it’s going to do. And it’s hard to observe. You need long, precise observations to understand its natural variability and how it responds to external influences.”

Yet these models supply most of our insight into how the weather might change when emissions raise the atmosphere’s CO2 component from 0.028% in preindustrial times to 0.056% later in this century. “I’ve been building models and watching others build models for 45 years,” he says. Climate models “are not to the standard you would trust your life to or even your trillions of dollars to.” Younger scientists in particular lose sight of the difference between reality and simulation: “They have grown up with the models. They don’t have the kind of mathematical or physical intuition you get when you have to do things by pencil and paper.”

All this you can hear from climate modelers themselves, and from scientists nearer the “consensus” than Mr. Koonin is. Yet the caveats seem to fall away when plans to spend trillions of dollars are bruited.

For the record, Mr. Koonin agrees that the world has warmed by 1 degree Celsius since 1900 and will warm by another degree this century, placing him near the middle of the consensus. Neither he nor most economic studies have seen anything in the offing that would justify the rapid and wholesale abandoning of fossil fuels, even if China, India, Brazil, Indonesia and others could be dissuaded from pursuing prosperity.

He’s a fan of advanced nuclear power eventually to provide carbon free base-load power. He sees a bright future for electric passenger vehicles. “The main reason isn’t emissions. They’re just shifted to the power grid, and transportation anyway is only about 15% of global greenhouse-gas emissions. There are other advantages: Local pollution is much less and noise pollution is less. You’re sitting in a traffic jam and all of these six- or four-cylinder engines are throbbing up and down burning fuel and just doing no good at all.”

But these are changes it makes no economic sense to force. Let technology and markets work at their own pace. The climate might continue to change, at a pace that’s hard to perceive, but societies will adapt. “As a species, we’re very good at adapting.”

The public now believes CO2 is something that can be turned up and down, but about 40% of the CO2 emitted a century ago remains in the atmosphere. Any warming it causes emerges slowly, so any benefit of reducing emissions would be small and distant. Everything Mr. Koonin and others see in the science suggests a slow, modest effect, not a runaway warming. If they’re wrong, we don’t have tools to apply yet anyway. Decades from now, we might have carbon capture—removing CO2 directly from the atmosphere at a manageable cost.

He’s less keen, except in the most extreme circumstances, on what many see as the cheaper, easier fix of augmenting the aerosol effect, which already partially offsets the warming caused by greenhouse gases, by injecting particles into the upper atmosphere. The political and practical unknowns are large. “You could have some country or even some individual do it. The policy community is just starting to grapple with that.”

Mr. Koonin does not drive an electric car. He drives what he jokes is the official car of Putnam County, a Subaru Outback, while he and his wife weather the pandemic in a woodsy enclave along the Hudson River. An Audi meant to haul them and the dog back to New York City, where he started and ran New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress, collects dust.

Mr. Koonin says he wants voters, politicians and business leaders to have an accurate account of the science. He doesn’t care where the debate lands. Yet his expectations are ruled by a keen sense of realities. I mention, along with some names, that I never met anyone of serious judgment who didn’t privately pooh-pooh the idea that humanity will control CO2 by means other than the mostly unregulated progress of markets and technology. Mr. Koonin nods his agreement.

He speaks of “could,” “should” and “will”—and what “will” happen is a lot less than elites, in response to current reward structures, are pretending will happen. Even John Kerry, Joe Biden’s climate czar, recently admitted that Mr. Biden’s “net-zero” climate plan will have zero effect on the climate if developing countries don’t go along (and they have little incentive to do so). Mr. Koonin hopes that “a graceful out for everybody” will be to see the impulse for global climate regulation “morph into much more impactful local environmental action: smog, plastic, green jobs. Forget the global aspect of this.”

This is a view widely shared and little expressed. First, the mainstream climate community will try to ignore his book, even as his publicists work the TV bookers in hopes of making a splash. Then Mr. Koonin knows will come the avalanche of name-calling that befalls anybody trying to inject some practical nuance into political discussions of climate.

He adds with a laugh: “My married daughter is happy that she’s got a different last name.”

Mr. Jenkins writes the Journal’s Business World column.