By

Alexander Lobrano

July 11, 2019 2:43 pm ET

LOOKING THROUGH the picture windows of the dining room at Marseille’s Les Bords de Mer, I took in the azure sweep of the Mediterranean. It was broken only by the bone-white Frioul archipelago on the horizon, and in the foreground, a few kids diving into the sea from high rocks. This might be a classic oceanside panorama in Provence, but the restaurant’s fastidiously white-and-blonde-wood décor revealed how much this southern patch of France has changed.

On my first trip to Provence, some 30 years ago, and in the dozens of visits since (it’s a three-hour train ride from my home in Paris), the hotels that awaited me were, by and large, theatrically rustic. Their spaces were dominated by faux farmhouse furniture, along with such totemic accessories as bunches of dried lavender in pitchers, floral-print bedspreads and ceramic grasshoppers. With these decorative conventions etched in my consciousness, Les Bords’s urbane minimalism jolted me right out of my Provençal stupor.

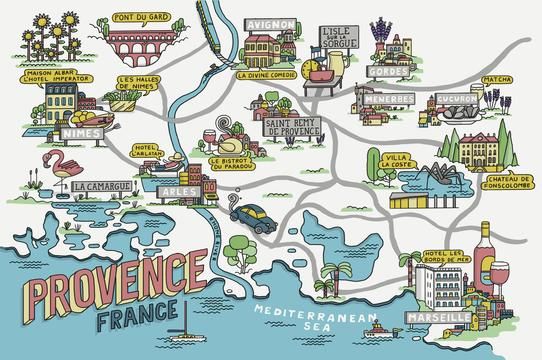

And it wasn’t the only surprise in store. Throughout the sprawling region—bordered by the Rhône River to the west and the Italian border to the east—new and dramatically renovated hotels are upending all the old stereotypes, touting cutting-edge art, architecture, design and cuisine.

From left: Newly reopened and dramatically renovated La Maison Albar Imperator in Nimes; grilled octopus and sweet pepper confit at MatCha. Photo: Clara Tuma for The Wall Street Journal

Hotel Les Bords de Mer (the white building on the seafront) in Marseille. Photo: Clara Tuma for The Wall Street Journal

To put this evolution in perspective, it helps to look at the provenance of Provence, or how this mostly rural swath became a Gallic Shangri-La. At the end of “Les Trente Glorieuses” (or Thirty Glorious Years), as the French call the postwar economic boom from 1945 to 1975, the geography of French leisure changed. Much of La Côte d’Azur, technically part of Provence but considered its own world, had become overbuilt, so Parisian tastemakers began looking inland, zeroing in on the then-sleepy villages of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Gordes and Ménerbes. These restless Parisians were following in the footsteps of artists like Cezanne and van Gogh who, in the early 20th century, dragged their easels from field to forest to cafe all over the region.

Illustration: JAMES GULLIVER HANCOCK

Then, in the late 1980s, a series of events lit the wick of a global yearning for Provence. In 1989, Peter Mayle, a former advertising executive, published “A Year in Provence,” a witty tale of renovating a house in Ménerbes and his indoctrination into the pastis-sipping, “if we don’t get it done today we’ll do it tomorrow” Provençal way of life, as seen through his British eyes. It became an international best seller. A year later, the magazine Maisons Côté Sud launched. This sumptuous ode to the languid pleasures of southern European lifestyles served as a manual for anyone aspiring to a life in sunnier climes. When France’s high-speed train line, the TGV, extended its reach to Avignon in 2001, it sufficiently shrank the travel time from Paris to make the region a weekend destination. Style mavens and celebrities flooded into Provence, including Pierre Berger and Yves Saint Laurent, who joined friends like French decorator Jacques Grange in Saint-Remy-de-Provence and fashion designer Pierre Cardin in Lacoste.

“After 30 years, it was time to turn a page. ‘Almost no one wants the pastiche version of Provence anymore,’ said one of the region’s innovative hoteliers.”

Suddenly the whole world wanted in. Dozens of hotels opened, strategically decorated to satisfy the fantasy of finding one’s own place in a sunbaked land of lavender and sunflower fields. Inevitably, a certain Provence fatigue set in. Smart-set French lifestyle magazines started vaunting the unspoiled if damper pleasures of places like Brittany as an alternative to Provence’s over-trammeled villages. After 30 years, it was time to turn a page.

Provence But Not Provincial

A look at the surprising new arrivals, dramatic renovations and the places stubbornly resistant to change

Louise Bourgeois’s ‘Crouching Spider,’ at Château La Coste, a 600-acre vineyard and open-air art park in Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, just outside of Aix-en-Provence. The art collection, first introduced in 2011, includes works by Alexander Calder, Tom Shannon, Andy Goldsworthy, Richard Serra, Frank Gehry, among many others.

Clara Tuma for The Wall Street Journal

1 of 24

“Almost no one wants the pastiche version of Provence anymore,” said Christophe Chalvidal, general manager of La Maison Albar Imperator in Nîmes. This legendary 1929 vintage hotel—where Frank Sinatra, Ava Gardner and Ernest Hemingway stayed when they came to Nîmes for the city’s bullfighting festivals—now describes itself as an “urban resort.” The 53 rooms and 8 villas come with oak parquet floors and palettes heavy in teal blue, gray and sand. The blue denim used for bed throws and some staff uniforms winks at the city’s past as the birthplace of the famous cotton fabric, whose name derives from de Nîmes (from Nîmes). As the bellhop who escorted me to my room put it, this is a big change from “a lot of dark furniture and wall-to-wall carpeting,” the hotel’s previous décor. You’ll find other departures at the hotel’s two restaurants, both run by Pierre Gagnaire, a three-Michelin-star chef. At the brasserie L’Impe, for example, the kitchen gives Nîmes’s sturdy signature dish, brandade de morue (salt cod and potatoes), a light, artful touch.

ADDRESS BOOK // Provence’s Chicest New and Renewed Hotels

Hotel L’Arlatan, from about $170 a night,arlatan.com

Les Bords de Mer, from about $280 a night,lesbordsdemer.com

La Maison Albar Imperator, from about $280 a night,maison-albar-hotels-l-imperator.com

Villa la Coste, from about $1,350 a night,villalacoste.com

Also, see “Classic Provence” below.

Seventy-five miles south of Nîmes, Marseilles is in the midst of an ambitious urban revival that’s drawn an influx of young creatives. This dynamism is why young hoteliers Frédéric Biousse and Guillaume Foucher settled on the city for their Les Bords de Mer. They bought a rundown art-deco hotel with a prime location and renovated it into a 19-room property with crow’s nest views of the Mediterranean. It opened last winter, and rooms, which come with small balconies, are almost all white and have a beach-shack chic. The restaurant serves refined, edgy fare like a salad of cuttlefish, white beans and pickled lemons. Ceramic grasshoppers and bouillabaisse are nowhere to be found.

From left: Bonnieux, a town in the Luberon region of Provence; Hotel L’Arlatan in Arles. Photo: Clara Tuma for The Wall Street Journal

In Arles, where van Gogh and Paul Gauguin lived for a time, Cuban-American artist Jorge Pardo redesigned the 34-room Hotel L’Arlatan, which reopened last October. “What fascinates me about Provence is the way it stimulates creativity. I think this comes from its layers of history, landscapes and light, but also the tension between tradition and invention,” Mr. Pardo told me. “L’Arlatan was a fantastic project, because Maja gave me carte blanche,” he said of the hotel’s owner Maja Hoffmann. The heiress to the Hoffmann-La Roche pharmaceuticals fortune, Ms. Hoffmann is developing an arts complex, Luma Arles, in an old rail yard, slated to open next year.

The 15th-century stone mansion that houses L’Arlatan was formerly the home of the Counts of Arlatan de Beaumont and is landmarked, which limited the scope for structural changes. Instead, Mr. Pardo turned the building into a backdrop for his paintings and added vivid tile floors, lamps made from recycled plastic and contemporary furniture. There’s also a restaurant run by Michelin-starred locavore chef Armand Arnal, and perhaps most surprising given the hotel’s design ambitions, a democratic range of summer room rates that begin at $170 and rise to $2,290 for a suite.

One of the suites at 28-room Villa La Coste. Photo: Clara Tuma for The Wall Street Journal

Contemporary art is also the driving force at Château La Coste, near Aix-en-Provence, where in 2011, Irish businessman Paddy McKillen first opened his spectacular open-air art park, in the middle of a 600-acre vineyard, to the public. Japanese artist Tadao Ando’s stark stone gate marks the entrance to the art park. Inside lurks a giant metal spider menacing a reflecting pool, the work of late French artist Louise Bourgeois. “Crouching Spider” shares the grounds with pieces by Alexander Calder, Andy Goldsworthy, Richard Serra, Frank Gehry and many others. In 2017, Mr. McKillen opened Villa La Coste, a 28-room hotel within the estate. Guests stay in low-slung limestone buildings overlooking the vineyards and art installations. Furniture runs to Scandinavian modern—the pedigreed good stuff by famous designers, not the big-box store knockoffs—with plump sofas wrapped in slipcovers and walnut étagères filled with art books.

The latest addition to Villa La Coste is a spa designed by Hong Kong architect André Fu. And in keeping with its all-star cosmopolitan lineup, Argentine grill chef Francis Mallmann oversees one of the three restaurants. But the most remarkable amenity is its ever-expanding art collection. As far as modern-day châteaus go, I can’t think of another place as indulgent as Villa La Coste. I’d happily spend a year sipping pastis on one of its terraces. Though, with room rates from $1,300 a night, I’d need to discover a long-lost van Gogh to afford it.

CLASSIC PROVENCE / Two Newly Spruced Up Hotels With That Old—Quite Old—French Country Charm

Château de Fonscolombe Photo: Clara Tuma for The Wall Street Journal

Château de Fonscolombe

After an 18-month renovation, the château (pictured below), a listed French historical monument just north of Aix-en-Provence, reopened this past spring. This is the place to indulge your inner aristocrat, so think ‘linen’ when you pack for a stay here. The public rooms of the Quattrocento-style, 18th-century château were scrupulously restored, right down to the original Chinese wallpaper and Genovese leather walls. The 50 guest rooms feature overstuffed armchairs and settees and thick jewel-tone curtains, all surrounded by 22 acres of classic gardens. From about $420 a night,fonscolombe.fr

La Divine Comédie

In Avignon, once you’ve visited the Palace of the Popes, the seat of western Christianity during the 14th century, leave the summertime crowds behind and head for La Divine Comédie, the luxurious boutique hotel that appeals as much to the sacred as it does to the profane. French interior designer Gilles Jauffret’s five-suite property opened in 2017 and occupies an 18th-century mansion surrounded by a sizable private garden. Each suite is individually decorated and furnished with a mixture of contemporary furniture and antiques. From about $500 a night,la-divine-comedie.com

A Brief, Atypical Guide to the Pleasures of Provence

The Sunday antiques market at L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue. Photo: Clara Tuma for The Wall Street Journal

The Market

TRIED AND TRUE: The Sunday market in L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, in the Luberon Valley, is sacred ground for antique hunters, and a great place to shop for everything from strawberries to an 18th-century mirror as long as you get there early—aim for 8 a.m.

UN-TOURISTY: Les Halles de Nîmes, a stellar food market, is open daily from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m. Grab a counter spot at La Pie qui Couette, a lunch-only restaurant inside the market, for hand-chopped steak tartare, grilled baby squid and local wines by the glass.

The ‘Next Big’ Area

TRIED AND TRUE: Long considered the wild west of Provence, Camargue is the luminous marshy delta region of the Rhône, just west of Arles, blanketed in rice farms and ranches. La Camargue’s capital, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, is a pilgrimage site for gypsies.

UN-TOURISTY: Le Gard departement encompasses the Pont du Gard, a Roman stone aqueduct; rolling hills that evoke Tuscany; Uzes, one of the prettiest towns in France; and the unsung city of Nîmes, with its new archaeology-focused Musée de la Romanité,

The Insider Table

TRIED AND TRUE: Since it opened in 1984, Bistrot du Paradou, in the village of Paradou, has been turning out excellent, classic Provençal fare, including dishes such as cod with vegetables and aioli and roast chicken. 57 Avenue de la Vallée des Baux

UN-TOURISTY: MatCha in Cucuron serves a suave modern update on the local cuisine—and a dining room where there’s still more French spoken than English. The menu runs to lighter dishes like mussels and fava beans in mint-seasoned bouillon. Montée du Château Vieux

Corrections & Amplifications

The Provençal village of Lacoste was misspelled as La Coste in an earlier version of this article. (July 12, 2019)

More in Off Duty Travel

- • 5 Mediterranean Islands the Tourist Mobs Haven’t Invaded Yet July 5, 2019

- • Venice Beach Souvenirs: A Discriminating Shopper’s Guide July 5, 2019

- • Manhattan to JFK in 8 Minutes? Hail an Uber Copter July 5, 2019

- • A Luxury Surf Vacation Where You’d Least Expect June 28, 2019

- • The Quirkiest Dining Scene in Berlin? Communist Comfort Food June 28, 2019

Copyright ©2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8